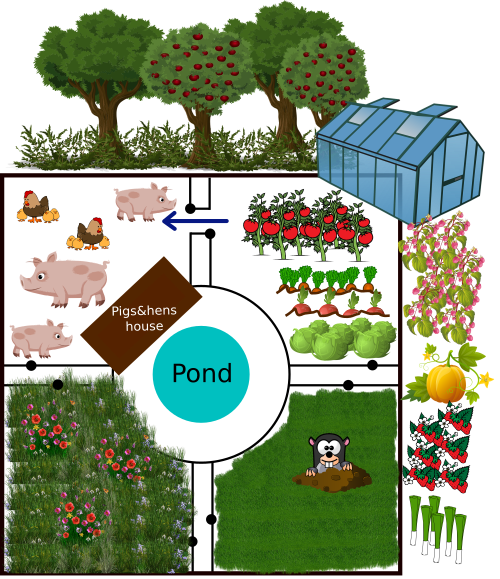

Example of a synergetic garden

Introducing a proven idea for a synergetic garden.

I'm going to explain this design in more detail, as it contains many elements.

The idea here, which corresponds to the synergetic approach to design, is to propose a solution for a garden, among others that could exist of course, that is productive, healthy and energy-efficient.

It's a model that I've been experimenting with for a whole year, and which has shown enormous advantages in terms of the time/yield ratio.

This kind of approach can also be found in permaculture.

The diagram above is an optimization of the model I tested.

First of all, this model should be seen as a cyclical one, proposing to occupy plots of similar size on a 4-year cycle. This seems to me to be the minimum acceptable.

Let's say that year 0 corresponds to the introduction of pigs and chickens into one of the four plots. These animals generally cohabit well together and complement each other: the pigs will literally plough the soil and nibble every root, and the hens will mainly eat tiny animals, including some of the pigs' parasites. Hen and pig droppings will also add fertilizer to the soil. The presence of pigs often deters hen predators. We can eat eggs, chicken and pork thanks to them (be assured that one adult pig is a lot of food, as long as we know how to process it correctly).

Year 1 corresponds to the annual vegetable garden. Here, you can sow and plant all crops that won't last more than a year. In temperate climates, these might include tomatoes, carrots, radishes, lettuces and so on. The previous work accomplished by pigs and hens helps a lot to start such garden.

Year 2 is the first year in which the previous vegetable garden is no longer maintained. Generally, some plants grow back, but most are quickly choked out by stubborn wild plants such as dandelions. This is the start of a fallow period.

Year 3 corresponds to the second year of fallow, and the plants found here are generally tougher and woodier. The following year, pigs and chickens will be introduced to this area to start a new cycle.

Around the plots are the perennial plants. These range from crops that have to be renewed every four or five years, to permanent bushes and trees.

A greenhouse can, in certain latitudes, help produce things that need heat and a more controlled environment than field crops. The greenhouse can be mobile if possible, so that you can alternate areas of land use. If it can't be moved, fertilizer will probably need to be added regularly.

The henhouse can be combined with the pigsty, and should preferably be mobile or at least easily dismantled and reassembled, so that it can be enclosed in the plots where the animals are kept.

The management of the central pond could be quite tricky, and may give rise to adaptations depending on the pigs' need to create a mud pond (most pig species greatly need it to hydrate, clean themselves and get rid of certain parasites).

However, the pond should never be used solely for pigs. In fact, pigs are generally quite destructive when it comes to water areas, and it's important for the garden that this water area also benefit plants and insects, particularly for pollination and pest management. Fences can be placed over the water to allow the pigs access without them being tempted to take over the whole area. It is also possible to prepare annual mud pond for the pigs, that will be relocated every time the animals are moved to another plot.

In addition, the plots should be carefully fenced off to prevent animals from entering at the wrong time.

Centrally-located paths and gates will make it possible to move around without wasting time, and to transfer animals from one plot to another without risk of escape!

When it comes to hens' tendency to fly and wander all over the place, there are two possible options:

high fences to keep them in the same plot as the pigs

high fences only on sensitive production areas, allowing the hens to roam wherever they please.

In all cases, it will be necessary to park the pigs, given their incredible destructive capacity!

The presence of trees around the production area is important for reasons of ecological balance and much more. In addition to fruit production, they offer innumerable advantages, as I have already explained in this article:

Depending on biotopes and climates, it may be possible to consider longer rotations, over 5 or 6 years. In any case, careful observation of the garden is the first reflex to have.

Water management can be optimized according to climate, with a rainwater recovery system installed directly next to the hen and pig hut.

This model should drastically limit, if not eliminate, the use of synthetic chemicals and significantly reduce the ravages caused by predators and parasites on plants and animals. It was the case when I tested it.

Some permacultural models combine the various plants shown on the diagram in a single area, and often remove some of them when they don't fit in well with the existing balance. These models work without animals and correspond to a vegan diet. Here, the model I'm proposing is omnivorous, so certain functions need to be adapted.

It is also suited to small to medium mechanized farming, with easy access to plots and the possibility of uniform treatment (a plot of wheat, for example). This adaptability of production seems to me to be important, as food choices and needs vary between people and over time. What's more, managing perennial plants on the periphery of the zone offers the opportunity to set up purely plant-based production zones of the permacultural type.

It's also a model that may be suitable for productions that will be marketed, although it is not compatible with an agricultural project whose productions are both specialized and intensive.